Thursday, 27 May 2010

Education, ejucayshun, eduKshn!

Recently, a new young thrusting Oxonian prime minister has been offering the British public negotiation, negotiation, negotiation. But 13 years ago the dawn rose over a previous young thrusting Oxonian prime minister and the solution he offered was the three-fold mantra of education, education, education.

It is a truism that education is key to unlocking potential and 3 years at Oxford has proven useful even for those of us who don’t end up as Prime Minister. But this month my thoughts have been far from those dreaming spires and, instead, closer to the coal face of education as it is found in South Africa.

For those looking for an education bargain, the independent colleges of Johannesburg – or better still the boarding schools nestling in the hills of KwaZulu Natal – provide fantastic value. First class facilities, classes of 20 students, highly qualified staff, committed and organised parents, and excellent co-curricula opportunities – all for a fifth of the price of the equivalent in the UK or US. And to assuage the consciences of those embarrassed by placing their children in a white ghetto, there are just enough non-white children to make the school photos look politically correct – though not so many that the ‘character’ of the school is lost. (In fact, I was told in all seriousness by one local parent that she had moved her daughter from a co-ed primary school to an all-girls secondary. While she wanted her daughter to have friends who were ‘African’ girls, she did not want her falling in love with some African boy. The final laugh would be if her daughter turned out to be lesbian!).

Unlike in other countries, the Jesuits do not run any schools here – their only South African school closed several years ago – but a number of the well-known private schools are Catholic foundations and try, some more successfully than others, to maintain a Catholic ethos. They are, of course, caught between the rock of good intentions and the hard place of competing in the market. Values are very important, say the parents, but the rugby fields and the exam results are what we are really paying for.

I have not yet had much to do with this part of the education world. But curiously an executive development programme that the Jesuit Institute was offering has turned out to be especially attractive to the senior management of some of the private schools. The course is designed to help people align their business organisations with their deepest values. In a symmetrical way, these schools are trying to align their values-based organisations with their business needs.

Meantime, the part of the South African education world with which I have had most contact recently has been the very opposite end of the scale: rural primary schools with classes of 50 or 60; often under-qualified teachers, un-engaged parents, dirt fields rather than astro-turf, and a constant struggle to scrape together enough budget to repair the windows, pay the teachers, buy some equipment. According to UN Development statistics, South Africa spends one of the highest % of GDP in the world on education, and yet some of these schools are only a few grades above what I witnessed in the refugee camps in Uganda.

At the invitation of the Catholic Institute of Education, I have been visiting and working with the principals of rural Catholic primary schools. Often these were mission schools, set up by a religious congregation decades ago, and now handed over to the community. They are termed ‘public schools on private property’ which means they get most of the benefits (and the bureaucracy) of being a state-funded school while retaining some of their distinctive character. They cater to the whole of the population of the village or the farm where they are which means that they rarely have more than 20%-30% Catholic students. And most of their children would come from families reliant on agricultural labour or ad hoc tourism. They thus struggle to get out of a vicious cycle of poverty, low aspirations, low skills and more poverty. With an added dose of alcoholism among those whose labours provide us with our grapes and oranges and Shiraz.

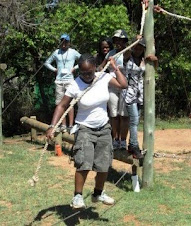

We have just started a 3-year programme to develop the leadership skills of the principals. Most of them have had little formation beyond teacher training and yet might still be the most formally educated person in the village. Because they are so isolated, we took out a road-show to 5 distant locations, some around the edge of South Africa (near Nambia, near Botswana, near Mozambique) and some dead in the flat arable centre of the Free State or the rolling hills of the Transkei.

The course is not rocket science – setting a vision, reflecting and journaling, peer support, identifying the few things you can change rather than getting bogged down in the ones you cannot – but I suspect that the main value of the first workshop was that these principals felt that someone cared enough to come and visit and encourage them. Whether that can produce material change we will see. The blocks that they face were all the worse since they were elements of the system that was supposed to be supporting them – incompetent Government officials, frequent changes of curriculum, inflexible unions, obstinate parish priests, unskilled governors, unusable policies.

But we did hear some good news stories: a young woman who had grown up on a farm school, had qualified as a teacher and then gone back as principal of the same school; a man who was recently struggling to pay for a family bucket at the local KFC until someone behind him in the queue offered to pay – the stranger who was now a successful doctor was someone he had taught 20 years earlier!

A quite different foray into the world of education has been a local counterblast to Dawkins. We have been running workshops for school students to show them that they do not have to choose between evolution and creation: they are completely compatible answers to 2 different questions. So it is possible that humans beings evolved from apes and yet are also ‘made in the image and likeness of God’. Invoking the great Jesuit palaeontologist, Theilard de Chardin, we are not trying to explain how human beings became spiritual but instead can just delight in the mystery that spiritual beings became human.

What is especially interesting is that this initiative was not ours but came from the Origins Centre at Wits University, one of the world’s leading fossil centres and where the recently discovered the 2 million year-old hominid, Sediba, is housed. Not something you could imagine the Natural History Museums in London or New York doing! But the scientists here thought this was a project worth investing in and needed some rational religious as their partners. The sight of a roomful of school-kids asking a priest about the sexual urges of the evolutionary dead-end that is the zonkey made me realise that this is just what the Jesuit Institute is good at.

Even without schools to run, we can bring to life the tradition of questioning and wondering that marks Jesuit education.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.